My Story

Deportations

When deportations began from the south of France in early August 1942, children under the age of 18 were exempted, and thus it was the official policy of the Vichy government to give parents the option of leaving their children behind. This option however, was rescinded shortly thereafter. Nevertheless, on the morning of my mother’s deportation, contrary to official Vichy policy, she was given the choice of taking us with her or leaving us behind. Although representatives of aid organizations working in the camps were able to save most of the children from deportation and death, there were days when children were deported along with their parents. There were also parents who, when given the choice, chose to take their children with them. Two-thousand-five-hundred men, women, and children were deported to Auschwitz from Camp Rivesaltes. Two hundred of these were children ranging in age from one through ten. It is only recently that I have researched my family’s flight and the rescue of my sisters and me. The documentation I have obtained from inquires I made to the French authorities shows our internment in Camp Gurs and Camp Rivesaltes. I also have a document that shows my father’s signature, giving his consent to place us in the care of the Jewish child rescue organization with the understanding that they would try to take us to Switzerland and safety. [Photo: Camp Rivesaltes, 2007.]

Nathan and Malcha Gutmann

My parents, Nathan and Malcha Gutmann, were among the more than 77,000 Jews deported from France between 1942 and 1944 by the Vichy government working in collaboration with the German authorities. Like my own family who had fled their beloved Berlin to seek refuge from the Nazis, many of these Jews were foreign-born. A great majority were murdered in Auschwitz. Jewish refugees were relatively, although not completely, safe while hiding in France until the summer of 1942. It was at that time that massive round-ups of Jews, especially refugee Jews, began throughout the country. The arrests came swiftly; most Jews had little or no warning. Removal to Drancy, termed the “antechamber of Auschwitz,” occurred quickly. The Vichy government, paid by the Germans to fill the trains with Jews, shipped them to the various Nazi concentration camps according to the timetable established by the German authorities. [Photo: My parents as newlyweds, 1930.]

Beginnings

The "other" girl named Ruth of my childhood lays frozen, in limbo over a large desolate plain in France, where the wind blows through what remains of the former camp barracks of Rivesaltes.

“Signed with friendly greetings.” My parents whom I never knew came to me neatly folded in somber gray envelopes. The memories of that other life shaped by my older sister Rita’s stories stir in me the image of a frightened and sad, little black-haired girl.

I have resurrected my murdered parents, and I lovingly recall my late sister Rita now in my senior years. But, Ruth, the name that was dangerously too Jewish, is the figure that never came to mind. She did not allow herself to be part of me.

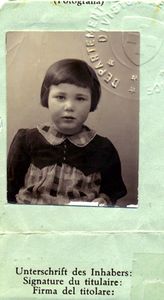

Born in Antwerp, Belgium in 1939 to Jewish parents who had been forced to flee their home in Berlin six months earlier, I spent my first three years in hiding with my family in the south of France. In the summer of 1942, with my father ill and bedridden by asthma, my mother Malcha, my two older sisters and I were arrested by the Vichy police, and shipped to the Rivesaltes internment camp. [Photo: My entry visa to Switzerland, 1943.]

Loss

On September 13, 1942, Rosh Hashanah, my mother Malcha, age 34, was selected for deportation to what the Vichy police said was a work camp, but was really a transport to Auschwitz, the death camp in Poland. My mother left us behind in the care of a stranger, a young woman, a nurse who worked with the clandestine child rescue organization known as Oeuvre de Secours aux Enfants, (OSE) walked us back to the empty barrack. Several weeks later, a Mademoiselle Rothschild also working with that clandestine rescue organization took us out of the camp.

Drancy, 1999

To this day, I do not know the circumstances surrounding my father’s capture in 1943. I have recently learned he was first held in the infamous Prison Fresnes, along with several hundred resistance fighters and downed Allied airmen. In February of that year, like my mother the year before, he was transferred to Drancy, a holding center for Jews in the Paris suburbs, and then deported to Auschwitz, where, like my mother, he was gassed.

Hiding

The convoyeuse took my sisters and me to a convent in Anncey. When the Germans occupied what had been unoccupied France in November of 1942, it became too dangerous for us to remain in the convent. Again we had to flee this time to the small border town of Annemasse, where with the help of the French resistance, we were passed illegally into Switzerland, where my father had a sister. We hid again. We were shuffled from distant relative to distant relative, exposed to physical abuse, hunger, and neglect. We were unwanted, and knew it. [Photo: Nye, France 1941. Mama, Papa, and me.]

Repression

When the war ended, we were brought to America. But my hiding continued there too. I was told my memories, scant as they were, were lies.

As a needy seven-year-old, I came covered with dirt and lice. A pathetic reminder to my mother’s brother, and his wife also a Holocaust survivor, my new family of all that they had lost.

Forget the past. Don’t speak of that other life. There was no one willing or prepared to hear the story that dominated my life. I was unable to attach my feelings to remembered experiences which caused me further suffering. Being silenced left me numb. Now I was hiding in full view. [Photo: Switzerland, 1945. Suzie (left), Rita (right), Sylvie (center).]

Coping

In 1993 with the death of my beloved sister Rita from Alzheimer’s-related dementia, I suffered a post-traumatic breakdown. I was 54. This was the break that would define or destroy me. My pain had been lying in wait for me. Not until this breakdown did a therapist have the wisdom to relate my inability to bond, to trust, or to love with the Holocaust, and my years in hiding. That the ability to make myself invisible, and adjust to being homeless, had left me unable to ever feel at home, or safe, or close to anyone. It seemed like my whole life had been lived in exile.

With the help of the New York Post, where my story made the front page, I was reunited with Mademoiselle Rothschild in Paris. It was the beginning of my 8-year journey back to my roots, my family, and to me.

It was in 2001, on the March of Remembrance and Hope, a leadership program for Jewish and Non-Jewish University students from the USA and Europe, where we would spend the week visiting the death camps of Poland. Having spent the day in Auschwitz, and back in the hotel, I was asked to share my survivor story with German students. What I encountered was there guilt and shame, and not the hate and anti-Semitism that I had feared. It was a turning point.

Berlin

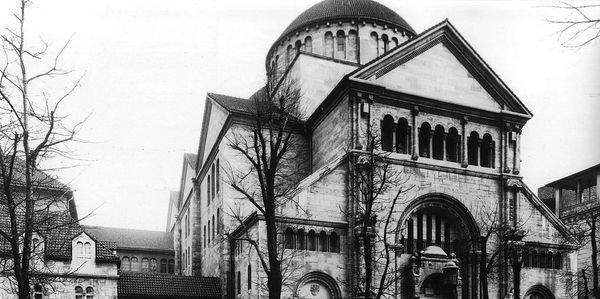

In 2002, I was given honorary German citizenship. It was then that I knew that I must go to Berlin to find the life (not only the death) of my murdered family. I rented a lovely apartment, and written on the lease by the owner with whom I had shared the fate of my parents was the following: “I hope that in this apartment you will find happiness and peace.”

On a cold December afternoon in 2005, 120 German friends stood with me by the entrance of Raumerstrasse 21 in Prenzlauer Berg, the house where my parents and 2 sisters had once lived, to commemorate the 2 brass Stolpersteine (Stumbling stones) that I had commissioned. On the stones is written: "Here lived Malcha and Nathan Gutmann." Followed by the year they were born, when and to where they fled, and where (Auschwitz) and when they were murdered.

I have been a Zeitzeugin (contemporary witness) and shared the story of my families fate to hundreds of students and various groups throughout Berlin. [Photo: The Stolpersteine in front of Raumerstrasse 21, Berlin, and the Stolperstein ceremony in front of Raumerstrasse 21.]

Jerusalem

March 2007, I am in Jerusalem, where I am reunited with an 83-year-old Lisl Hanau, the young nurse to whom my mother gave her 3 precious daughters in camp Rivesaltes. She hands me a picture from her album which shows me, a lonely and sad 3-year-old, taken after Mama was shipped away.

Rivesaltes, September 1942: Sylvie (bottom left), Rita (2nd row, 3rd from left), Susi (back row, 5th from right), and 18-year-old Lisl Hanau, our rescuer (half visible, far left).

It is December 13, 2007, 150 people stand with me on Barnimstrasse 38 and 18, the former homes of my murdered grandparents, Chava and Markus Gutmann, and my uncle and aunt, Levy and Bertha Gutmann, where four Stolpersteine have been laid.

With the laying of these stones I have returned my family to the city they loved and called home, and on December 25, 2007, I will return to the place I love and call home: America.

Copyright © 2020 Sylvia Ruth Gutmann - All Rights Reserved.

Powered by GoDaddy Website Builder